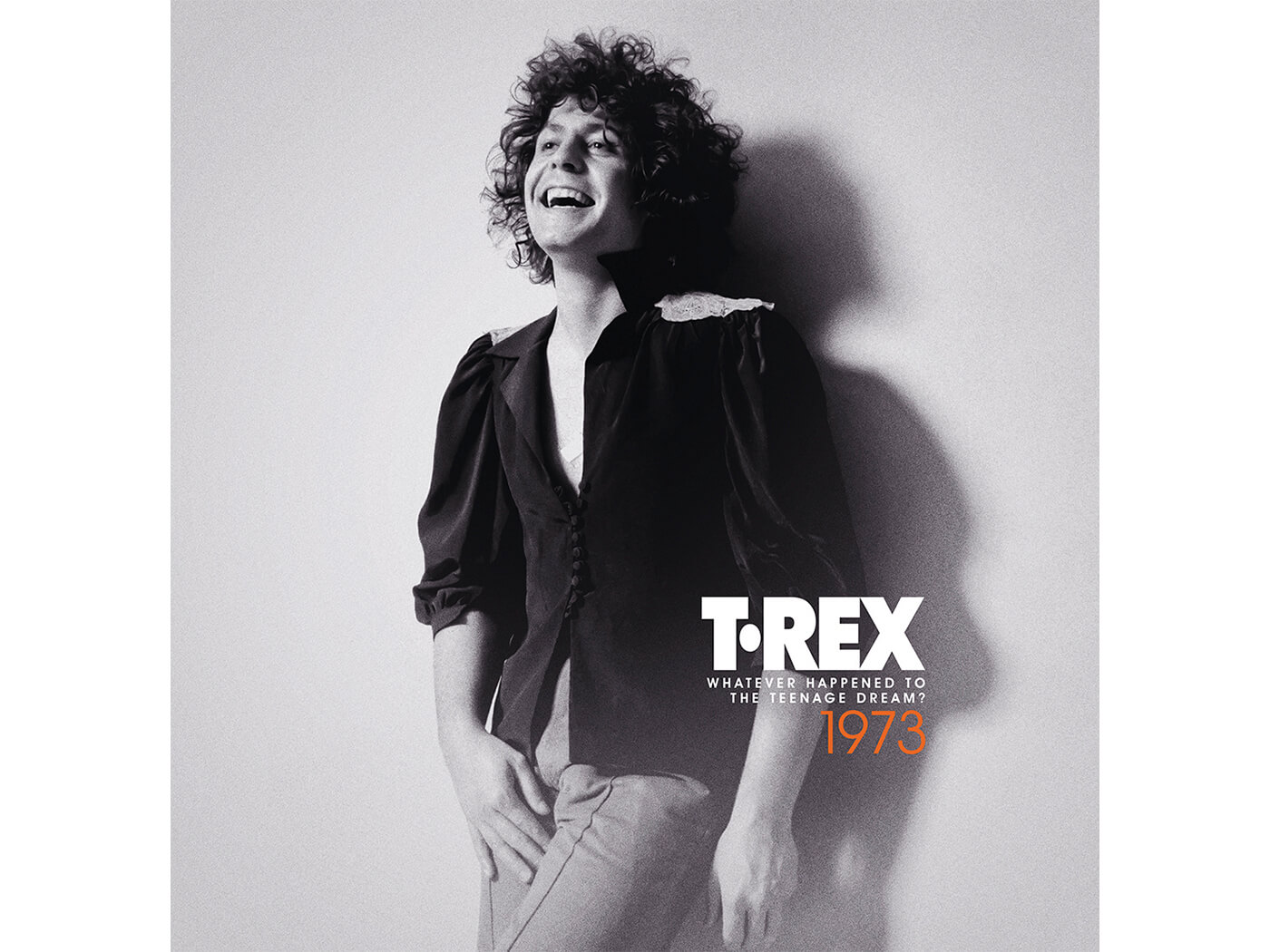

Steve Priest of The Sweet once suggested that glam rock began with Marc Bolan wearing a pink feather boa. From this moment of camp inspiration a gloriously absurd movement was born, and Top Of The Pops was transformed into a crowd-scene of hod-carriers in Bacofoil trousers.

For Bolan, the association was a mixed blessing. If glam rock was – to quote David Bowie quoting John Lennon – “rock’n’roll with lipstick on”, Bolan’s position at the centre of the mania came via a convoluted route. He had been a mod, abandoning the look by 1965, and adding a sprinkling of psychedelia in John’s Children. Tyrannosaurus Rex were mystical hippie minstrels, before abbreviating their name and condensing their appeal. A string of huge hits for T.Rex began with “Ride A White Swan” in 1970, and the whirlwind of commercial inevitability which publicist BP Fallon called T.Rextasy continued through 1971, reaching a peak of sorts when T.Rex played two shows in one day at the Empire Pool, Wembley, in March 1972. The film of their two shows, Born To Boogie, was directed by Ringo Starr and was hailed as a passing of the torch, from The Beatles to T.Rex. On its release, Bolan dubbed himself “Cecil B deBolan” and talked airily about filming a sequel.

And yet. And yet. Being at the eye of a phenomenon is not a long-term plan, and Bolan’s private life was beginning to show the strain. In the sleevenotes of this 5LP/4CD box, biographer Mark Paytress notes that in 1972, Bolan talked of becoming a recluse, developed a dread of plane crashes and entertained the probability that he would die young. In October 1972, he had suffered a breakdown which was characterised as a “partial heart attack”. Cognac and cocaine binges delivered “crushing downsides”.

In the midst of these insecurities, Bolan wrote a musical memo to himself on a scrap of paper: “space age funk”. It’s an idea that would find its place and time. Bolan’s contemporary and rival, David Bowie, would get there soon enough. Decades later Prince would crush Bolan’s elfin androgyny into dynamic new shapes. For Bolan, the concept would remain half-realised, an evolution too far. It would also have been a mistake, a category error which ignored Bolan’s more obvious gifts. Happily, in failing to deliver on his promise to himself, Bolan produced some of his most enduring music.

We should start with the singles. In 1973, popular acts made hit 45s, and credible artists made albums. There are two albums on this box, Tanx and Zinc Alloy And The Hidden Riders Of Tomorrow. One of these is very good, and was released with a fold-out poster of Bolan sitting astride a phallic toy tank. The other sounds like an attempt to follow David Bowie down a theatrical side-street.

The singles, though, require no explanation. They are signed, sealed and delivered with such boastful aplomb that they mock any attempt to unpick their appeal. They are pop songs about pop, sugar-coated and boastful. “Solid Gold Easy Action” is glitter beat without Gary, spliced into a chorus which appends “easy action” as the solution to The Rolling Stones’ complaint about their dissatisfaction. (The song also contains the seed of Adam Ant’s entire career.) Likewise, “20th Century Boy” is two or three explosions combined. There’s a thunderous riff, a yelp, an exaltation. “Babe, I wanna be your man”, Bolan sings, quoting pop music as surely as he inhabits it. And then there’s “The Groover”, with its fabulously arrogant opening chant – T!R!E!X! – before the song swells into a warped gospel hallelujah. The influence of producer Tony Visconti, who also guided Bowie’s sound, is obvious, but the inclusion of Bolan’s demos shows how resilient the songs are. “Jitterbug Love (Demo)” is a cosmic treat. “Electric Slim & The Factory Hen (aka You Got The Look) (Demo)” has wiry charm. The solo rendition of “The Groover” reveals the bluesy architecture of the tune.

And space-age funk? Well, there’s a bit of Sly Stone in “20th Century Boy”. It’s a small mercy that the world ignored Bolan’s suggestion that the song marked the birth of a new genre, Erection Rock. His more soulful leanings are explored in the recordings he made with singer Sister Pat Hall, which have Bolan’s gospel kinks pushed to the forefront. They’re not without merit – “Ghetto Baby” contains the kernel of George Michael’s entire career. But they’re not T.Rex. Bolan’s interest in gospel and soul was influenced by his relationship with Gloria Jones, but there’s a mismatch between Bolan’s pop sensibility and the excitations of gospel. “Sky Church Music (alt version)” is a demonstration of what happens when a singer finds himself in the awkward position of being both lost and found.

So, what happened to Marc Bolan in 1973? The final track arrives as a solemn postscript: a recording of “Teenage Dream” as performed on Top Of The Pops on February 7, 1974. Sonically, it could be better. The tune phases in and out like a rented TV with a coat-hanger aerial. Musically, the dream is fitful, weary and jaded, with Marc Bolan sounding suddenly adrift from the easy brilliance of his younger self.