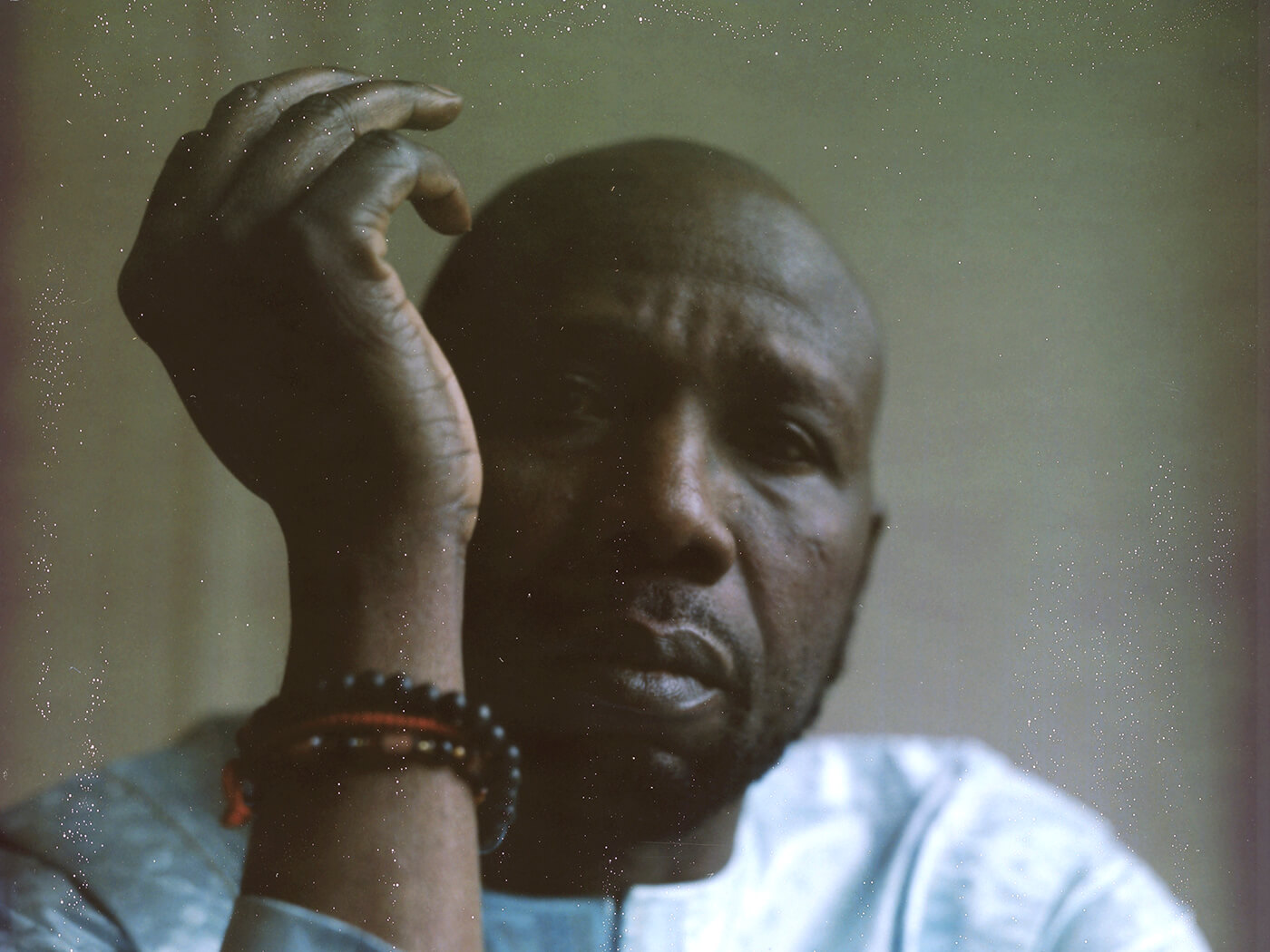

Given he plays an instrument that makes such serene and tranquil music, Ballaké Sissoko has encountered an awful lot of people hellbent on smashing his kora. First, there were the Islamic terrorists who overran northern Mali and destroyed every musical instrument they could find. Happily, Sissoko’s kora escaped this jihadist intolerance, but he was less fortunate at the end of his 2020 American tour, shortly before the world locked down.

After he had checked in for his homeward flight, customs officials decided to give his kora a brutal shakedown. On landing in Paris the instrument was returned to him in pieces with a note from the US Transportation Security Administration stating that it had been dismantled for “inspection purposes”. There was no apology and the note came on letter-headed paper bearing the ironic motto: “Intelligent security saves time.”

Back in Mali he rebuilt the instrument and set about completing the recording of Djourou, a labour of collaborative love on which he had begun work in 2018. Oxmo Puccino, the French rapper who is one of the many guests on the album, offers a striking description of working with Sissoko. “When he plays it’s like a ballet of fingers on strings,” he says. “It’s as if he’s knitting the music together.” The analogy is a fitting one. Keith Richards likes to refer to his guitar duets with Ronnie Wood as “the ancient art of weaving”, and with 21 strings to his kora, Sissoko has more strands than most with which to weave his spells. On Djourou – a Bambara word meaning ‘string’ – he entwines musical threads with a diverse range of fellow travellers from a multitude of cultures and genres to crochet a sonic patchwork of vivid hues and exquisite patterns.

Sissoko ranks behind only his cousin Toumani Diabaté as the world’s pre-eminent kora player. Their respective fathers Djelimady Sissoko and Sidiki Diabaté were also the leading virtuosi of their generation and in 1970 recorded Cordes Anciennes together, the world’s first instrumental kora album. Twenty years later, Ballaké and Toumani combined their own prodigious talents on New Ancient Strings, a dazzling set of kora duets conceived as a homage to their fathers and which launched Sissoko’s international career.

Yet in addition to classical solo recordings, Sissoko has become an intrepid cross-cultural collaborator, insinuating the kora’s unique sorcery into new contexts. Over the past two decades he’s recorded with the US bluesman Taj Mahal and the Italian composer Ludovico Einaudi, made a brace of deathless albums with the French cellist Vincent Segal and stitched together bespoke global fusion projects with traditional string musicians from Morocco, Madagascar, Greece, Afghanistan and India.

His last solo album, 2013’s At Peace, was a typically adventurous affair that featured duets with cello and guitar alongside gentle solo kora pieces and included Brazilian as well as African tunes. Recorded in half a dozen different locations, Djourou is even more expansive and was conceived as an album of unexpected collaborations, as Sissoko deliberately sought out partners who for the most part have little or nothing in common with the rich Malian griot heritage on which his music draws.

The opener, “Demba Kunde”, is one of just two solo kora pieces, full of stately elegance before it gives way to the rococo classicism of the title track, a duet with Gambia’s Sona Jobarteh, whose pioneering role as a rare female kora virtuoso joyously subverts the stifling hierarchy of African patriarchy. Tender yet majestic, “Guelen” is a sacred praise song, with Sissoko’s rippling kora exquisitely underpinning the soulful, soaring tones of the golden voice of Salif Keita.

So far so traditional, but it’s on “Jeu Sur La Symphonie Fantastique” that things start to get really interesting, as Segal’s cello and Patrick Messina’s clarinet join Sissoko’s kora to take Berlioz’s romantic masterpiece on a dreamy voyage down Mali’s great Niger River. Yet the real surprises are held back for the album’s run-in. “Kora” is a sublimely haunting love letter to the beauty of Sissoko’s instrument featuring the breathy, sensuous voice of Nouvelle Vague chanteuse Camille.

Over Sissoko’s baroque kora curlicues, “Frotter Les Mains”, recorded in a locked-down Paris in July last year, finds Puccino rapping in a deep and languorous voice about the lost pleasures of touching in a socially distanced world. Piers Faccini offers a more lyrical vocal style, poignant and full of nostalgic longing on the gentle ballad “Kadidja” before the album concludes with Arthur Teboul and French oddball experimentalists Feu! Chatterton adding some delightfully madcap psych-folk weirdness to Sissoko’s spritely playing on “Un Vêtement Pour La Lune”.

The result is an album of glorious hybridity, rooted in ancient griot tradition but serendipitously transformed into an audaciously cosmopolitan melting pot.