Watching Smokey and the Bandit all these years after its release is an exercise in cultural anthropology. Even more so than other films of its time, this 1977 car-chase comedy drops markers about its time and place like spent auto parts falling from a pursuing police cruiser.

The film’s plot, to the extent that it has one, rests on the fact that the Coors Brewing Company didn’t pasteurize its beer. That meant that the beer would spoil in a week or so without refrigeration, limiting distribution from the company’s Colorado headquarters. The movie kicks off with a sheepish Georgia trucker being told that his rig full of Coors constitutes bootlegging and that he’s just another sucker, having accepted a bet from local father-son duo Big and Little Enos Burdette to illegally import the stuff.

Played by Pat McCormack (Big Enos) and singer-songwriter Paul Williams (Little Enos), the Burdettes are the first of the film’s raft of broadly drawn southern stereotypes, as they persuade Burt Reynolds’ local celebrity trucker the Bandit (real name Bo Darville, as pieced together from isolated lines in the film) to accept their wager of a whopping $80,000 if he can complete the 28-hour round trip from Texas.

The story, written on legal pads by Reynolds’ friend, the former stuntman turned director Hal Needham, is essentially just that, as Bandit cajoles his truck-driving pal Cledus (singer Jerry Reed, rattling on as one of cinema’s best sidekicks) to drive Bandit’s big rig. Bandit himself will be driving “blocker,” another of the film’s conceits viewers (most of whom are not prone to high-speed pursuits) are tasked with putting together from context. Essentially, Bandit, after getting the Burdettes to peel off thousands of dollars from the wad of hundreds in Little Enos’ pocket, will tear-ass in the vicinity of Cledus’ speeding 18-wheeler in his newly purchased black Pontiac Trans-Am, attracting police attention and leaving Cledus free to steam his illicit cargo straight through to Georgia.

Technically following the then-popular movie trend centered on fast cars and incomprehensible trucker lingo shouted into CB radios, Smokey and the Bandit truly shifted the genre into high gear, ushering in several years of squealing tires and smashing police cars emanating from drive-in speakers. Opening first in New York, the modestly budgeted ($4.3 million) picture started slowly, but, on the back of a regional rollout through the south, gained enough traction to wind up as the year’s second-highest-grossing film. (Only Star Wars beat it, with Smokey taking in $126 million to Star Wars’ record-breaking $221 million.)

That makes sense. Certainly, Burt Reynolds was the film’s major selling point, Reynolds had already cemented both his auto racing and southern action star cred in films like White Lightning and its sequel Gator, and W.W. and the Dixie Dance Kings. But Smokey and the Bandit codified Reynolds as a specific type of good-old-boy superstar. That later became something of a curse, as Reynolds continued to mine the image of him as a rakish speed demon in Needham-directed films like the first Smokey sequel (he did pass on the third, making only a cameo), Cannonball Run and its sequel, and the widely derided 1983 NASCAR comedy Stroker Ace. To take the part in the latter film, Reynolds passed on James L. Brooks’ Terms of Endearment, with the role scoring an eventual Oscar for Jack Nicholson.

Watch the ‘Smokey and the Bandit’ Trailer

None of that, however, can take away from the absolute charisma machine that is Burt Reynolds as the Bandit. Fifteen minutes into the film, when Reynolds and his Trans Am ditch the first of what will be dozens of futile police pursuers, the actor gives a fourth-wall-breaking look right into the camera, Reynolds’ signature delighted giggle indicating not so much that viewers are in on the joke, but that Burt Reynolds, at that point in his career, could do anything he wants.

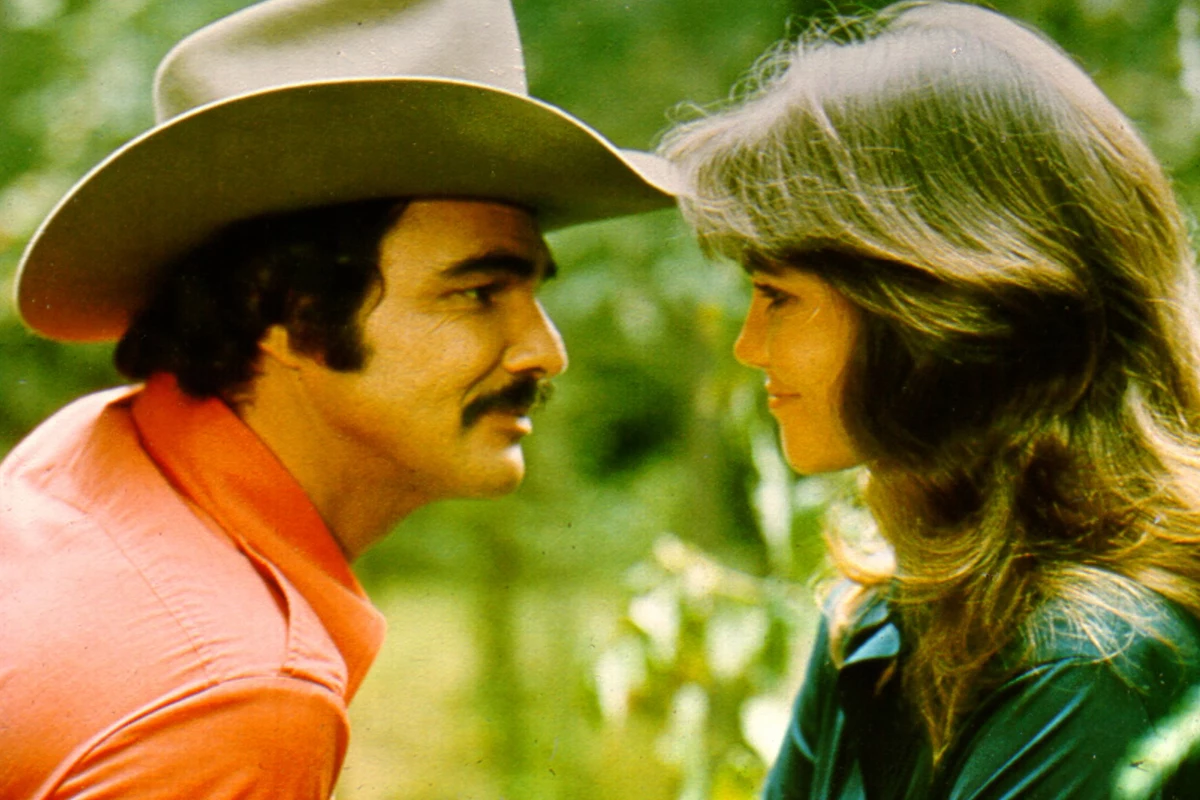

And he can. Flagged down by runaway bride Sally Field soon after, Reynolds whisks the fast-talking young woman along on his mission, the pair immediately falling into wise-cracking repartee that would come off as glib if not for how off-the-cuff their jabs feel and how obvious the actors’ offscreen attraction was. Shortly before his 2018 death at age 82, Reynolds, in an interview, called Field the love of his life. Field, who met the 10-years-older Reynolds on Smokey and dated him on and off until 1982, stated in her 2018 memoir that their romance was a lot more complicated (and problematic) than that. But in the film, their chemistry is spiky, fresh and delightful.

Bandit gives his passenger the CB moniker “Frog” at one point, thanks to her penchant for hopping around the Trans Am’s interior (and because, he cracks, he wants to “jump her.”) But while the sparks inevitably fly (the pair even taking precious time out of their cross-country spree to pull over and make love), Reynolds and Field form a truly irresistible partnership. Reynolds initially called Needham’s script the worst he’d ever read, and he, Field, Reed and especially Jackie Gleason’s deliciously hammy and obsessed Texas lawman Buford T. Justice all improvised freely, something the trained and younger Field first balked at.

In the movie, though, her flirtatious banter with Reynolds (usually while the wind whips through the open T-tops of Bandit’s speeding Trans Am) comes off as spontaneous and funny. Destined though she might be to fall for this handsome outlaw, Field’s Frog (who is on the run from an aborted wedding to Justice’s lunkheaded son, Junior) tries to rationalize her attraction, at one point vainly seeking to find out a single thing they have in common. Striking out (she’s never heard of Richard Petty, while he doesn’t like Elton John), Bandit offers up a piece of down-home wisdom persuasive enough for Frog to ask him to finally take off his hat. (Which he only does “for one thing.”) “When you tell somebody something,” Bandit states, “it depends on what part of the United States you’re standing in as to just how dumb you are.”

That sentiment goes a long way toward papering over some of our modern misgivings about the film’s cultural markers, too. While Reynolds and Reed both are shown having friendly interactions with Black people they meet along their journeys (Bandit with an admiring gas-station attendant, Cledus with the proprietor of his favorite watering hole and another trucker named Sugar Bear), the Trans Am sports a prominent Confederate flag as part of its front license plate. Justice, who earlier in the film calls a Black law enforcement officer “boy” before moaning to Junior about what the world’s coming to, also promises to “punch your mama in the mouth” upon their return home, Gleason memorably ad-libbing to the dullard, “There is no way that you come from my loins.”

Then there’s the fact that Bandit (and Frog, who commandeers the Trans Am for a bit) are ridiculously reckless, all their bridge-jumping and bootlegger turns seeing them nearly running over an entire peewee football game and perpetrating untold property damage. (Woe to any citizen on the Bandit’s route with a roadside mailbox.) Nearing their goal, and with an army of cops (including a helicopter) on their tail, Frog asks Bandit worriedly if he’d expected all of this. “No, I didn’t honey,” Bandit admits. Earlier in the film, Field’s Frog (her actual name is Carrie) cuts him off mid-banter, asking Bandit what, exactly, he is good at. “Showing off,” he replies with a grin, Reynolds allowing just enough of a peek inside this “legend” (as Cledus calls him) for the actor’s signature vulnerability to peep through.

Watch a Scene From ‘Smokey and the Bandit’

Like Clint Eastwood’s bare-knuckle boxer in the following year’s similarly southern-fried knockabout road movie Every Which Way but Loose, Bandit is, indeed, a uniquely rural American sort of legend. The kind whose law-baiting, hard-living, decidedly physical prowess makes him beloved of throngs of regular people, who build him up as a folk hero. The CB element sees Bandit’s exploits gaining so much attention that other drivers come to his aid in evading police, while a gaggle of southern roadside beauties holds up a banner cheering him on.

The inferior Smokey and the Bandit 2 from 1980 delved into how Reynold’s Bandit starts to believe his hype, but, here, it’s enough for Reynolds to merely allow us the occasional glimpse of Bo Darville, before becoming the Bandit once more. It’s a trick Reynolds the actor deployed with decreasing success as his career declined and his carefully manufactured public image (which feels innate and effortless here) grew tougher to maintain. But in this enduringly enjoyable vehicle, at least, Burt Reynolds could do no wrong.

The Best Rock Movie From Every Year

A look at the greatest biopics, documentaries, concert films and movies with awesome soundtracks.