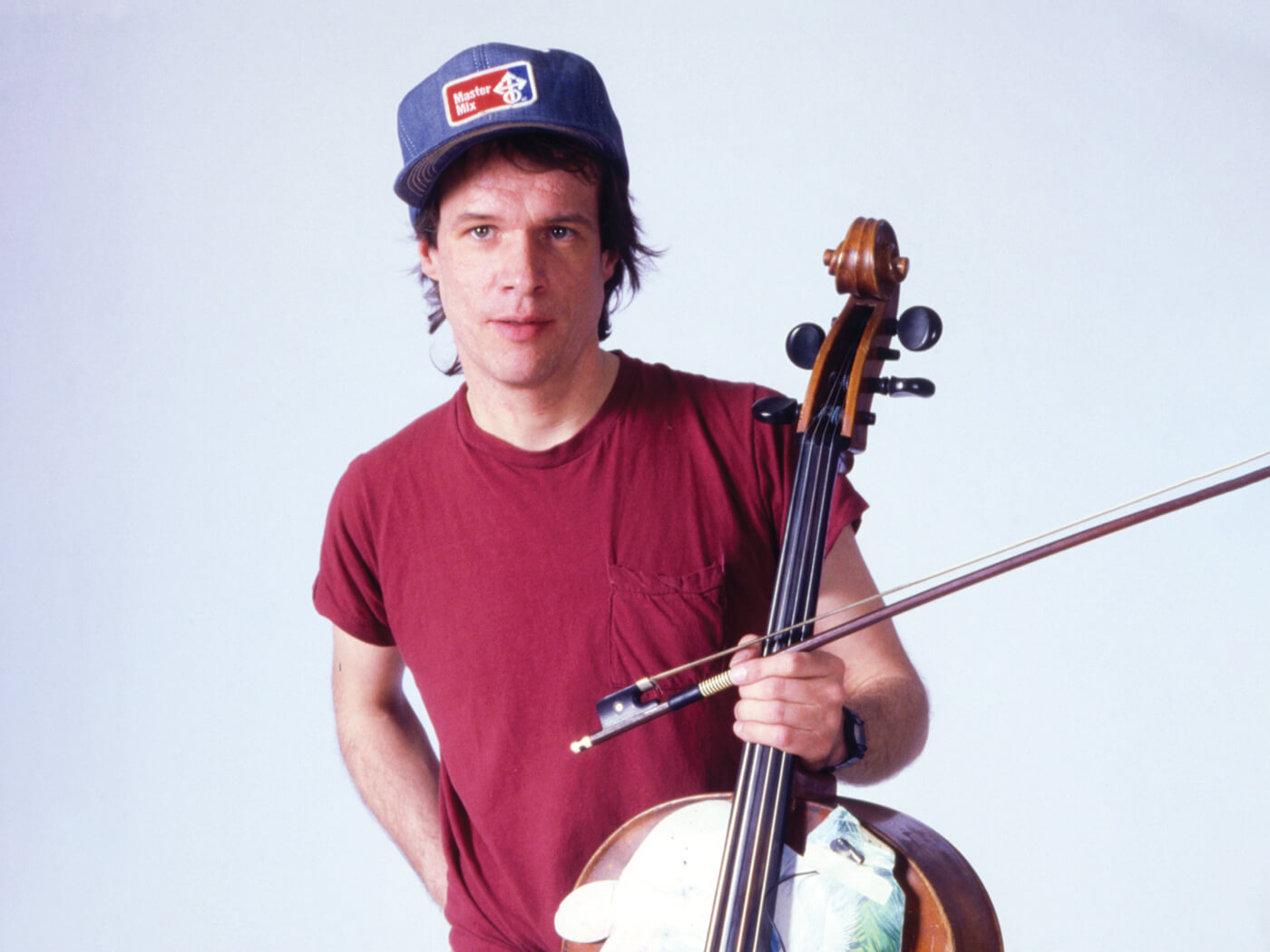

Thirty years after his Aids-related death, aged just 40, Arthur Russell’s music still has a luminous freshness and richly emotional power. The cult composer, cellist and downtown New York scene-hopper amassed a vast body of work spanning avant-classical chamber pieces, disco and dub, experimental electronica, folksy Americana and Buddhist bubblegum pop, but he released very little solo material in his lifetime. Russell’s radical queerness and genre-blurring musical promiscuity confounded peers and record labels, but he also stifled his own potential with painstaking perfectionism, endlessly hoarding and reworking pieces that deserved a public airing.

Russell’s posthumous reputation has blossomed over the last two decades, his legacy celebrated in books and films, his songs sampled by Kanye West and covered by Tracey Thorn, Hot Chip, Sufjan Stevens and more. This resurgence is largely thanks to the meticulous efforts of his former partner Tom Lee, designer Melissa Zhao Jones and Steve Knutson, boss of Portland-based boutique label Audika, who have assembled an ongoing series of mostly glorious anthologies excavated from Russell’s massive tape archive. In partnership with Rough Trade, these Audika albums are finally receiving a full physical launch in Europe.

First released in 2004, Calling Out Of Context became a key early stepping stone in Russell’s critical rediscovery and wider dissemination to a new, younger audience. Lovingly packaged and curated, it combines tracks from his unreleased 1985 album Corn alongside archive material that he spent years honing for a long-promised, forever-delayed release on Rough Trade. As an entry point into Russell’s sprawling canon, the music is impressively high calibre but hardly comprehensive, emphasising his art-pop singer-songwriter side over his club-friendly or contemporary classical work. That said, these slippery compositions still range freely across genres, inventing a few new ones along the way.

Cautiously embracing the dominant new wave and electro-pop aesthetic of the era, Russell deploys drum machines and synthesisers alongside regular human collaborators including trombone/keyboard player Peter Zummo and percussionist Mustafa Khaliq Ahmed. But like almost everything he recorded, these semi-mechanised tunes also feel warmly organic, soulful and sensual, with an emphatically human heartbeat. There is a seductive smalltown sweetness to Russell’s airy narcotic reveries, his stream-of-consciousness lyrics peppered with nostalgic yearning for the wide-open skies and lakes of his Iowa childhood, notably on the deliciously woozy “That’s Us/Wild Combination”. He radiates boyish innocence, even when hymning his carnal intoxication with sex in the serotonin-drenched funk-pop earworm “Get Around To It”.

On “Calling Out Of Context” itself, with its bustling urban-tropical percussion and jittery art-rock jangle, Russell stakes a claim in the avant-world terrain explored by his New York contemporaries and sometime collaborators Talking Heads. The skeletal lo-fi Toytown disco-pop of “Make 1, 2” and infectiously weird “Hop On Down”, a slinky sunshine groove punctuated by bursts of electromagnetic crackle, could almost be Prince at his most experimental. The fact that Russell envisaged both as possible singles shows just how forward-thinking he was, or perhaps how gloriously unmoored from commercial reality.

Heard through 21st-century ears, it is striking just how contemporary much of this music sounds almost 40 years later. With their hypnotic machine rhythms, drones and throbs and loopy vocal ripples,“The Platform On The Ocean” or “Calling All Kids” feel like prescient blueprints for Radiohead’s mid-career post-rock rebirth. Meanwhile wafting, weightless, loose-limbed dream-funk confections like “You And Me Both” or “Arm Around You” could easily be the work of some hip millennial electro-soul soundscaper on XL or Erased Tapes.

Drawn from live work-in-progress performances spanning 1975 to 1978, Instrumentals first appeared in botched and truncated form in 1984. It took another 33 years before Audika unveiled this expanded, lovingly restored, double-album version in 2017. The project has esoteric roots: inspired by the photography of his Buddhist teacher, Yuko Nonomura, Russell had an epiphany that opened his ears to the magical, transcendent power of American bubblegum and easy-listening music. The untitled compositions spanningVolume 1are mostly mellifluous lo-fi chamber-pop pieces steeped in wide-eyed Americana, their bluegrass twang and jug-band honk overlaid with crackle and feedback and dubby dissolves. There are echoes of Copeland and Ives, Gershwin and Bernstein here, but also Brian Wilson and Beirut’s Zach Condon.

Volume 2 of Instrumentals consists of a more polished, expansive, symphonic piece played by the Brooklyn Philharmonic’s CETA orchestra, a gorgeous pastoral sound-painting couched in silken strings and mournful brassy fanfares. The conductor is Julius Eastman, another overlooked queer polymath on the fringes of New York’s 1970s minimalism scene. Rounding off this selection are two of Russell’s most uncompromising sonic experiments, both recorded live in 1975. “Sketch For The Face Of Helen” is a musique concrète collage of drones, analogue electronics and the sampled roar of a Hudson river tugboat, while the proto-ambient tone poem “Reach One” features two Fender Rhodes pianos engaged in a drowsy, gently ebbing dialogue.

Fastidious listeners might nit-pick a few repetitions, audio glitches and overstretched ideas across these albums. But as an overall listening experience they are voluptuous, immersive and soul-soothing. Russell’s spellbinding music seems to float in its own beatific glow, always generous, never demanding, forever fluid, rarely fixed. There are whole continents of sound contained in these two collections alone that a curious explorer might easily get lost inside, perhaps never to emerge again.