If rock fully sparked into life in the mid-’60s, then those pioneers are now well past collecting their pensions. Some are gone, of course, others creatively spent. A select few, over the last few years, have entered a new creative realm: here, the white-hot urgency of youth is regained, this time tempered with the wisdom of age and the bittersweet passing

of time. The results have been stunning: there’s Rough And Rowdy Ways, of course, and Blackstar, along with Leonard Cohen’s final trio, Roy Harper’s Man & Myth, McCartney III, Bill Fay and Mavis Staples’ recent work, and so on. When an album may be your last, there’s every reason to not go quietly into that good night.

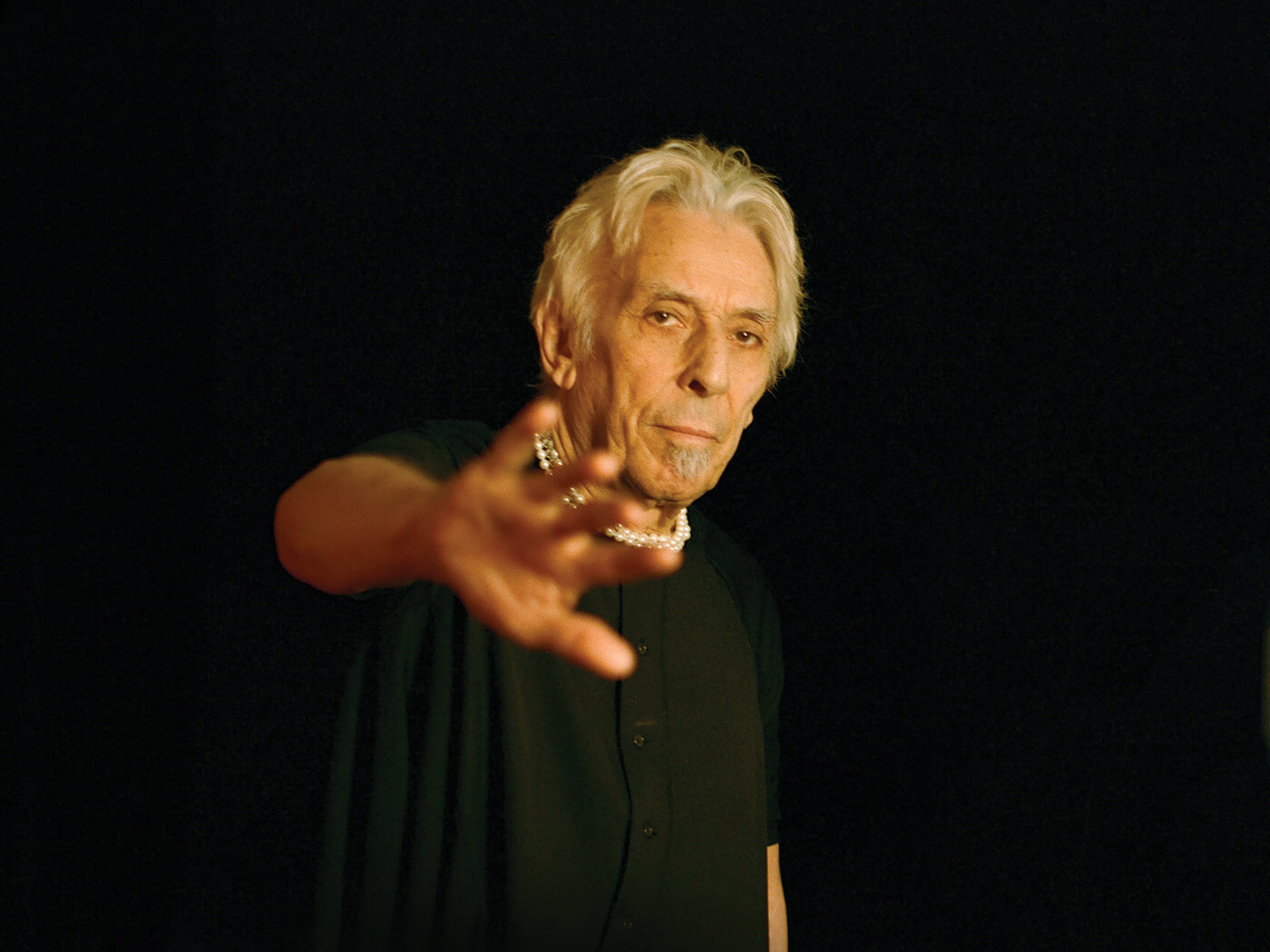

When a latterday masterpiece is a chance to either distil your craft or launch into wild new adventures, it’s no surprise which of those Cale has gone for on Mercy, his first album since 2012’s Shifty Adventures In Nookie Wood. If a reminder is needed, this is the experimentalist who left Wales for New York City, who played in La Monte Young’s Theatre Of Eternal Music, who brought much of the pioneering squall to The Velvet Underground and changed rock music, who stuck with Nico and helped her make some incredible solo albums, and who produced pivotal records by the Stooges, Patti Smith and Happy Mondays.

Of course, he’s never stopped experimenting: two decades ago he got into hip-hop through Snoop Dogg’s “Drop It Like It’s Hot” and, pushing 81, he’s still enraptured by Earl Sweatshirt, Kendrick Lamar and Chance The Rapper. This century, his music has been invigorated, with 2005’s rocky BlackAcetate and its future-funk follow-up among his best. He’s spent the last decade honing his live craft, delving into his whole catalogue, and reassessing past triumphs, most notably on 2016’s M:FANS, a reworking of 1982’s Music For A New Society.

All that now feels like taking stock before pushing off into the great unknown – for Mercy is the most out-there work Cale has made in some time, a hermetically sealed, hallucinogenic journey that’s as neon-lit and gothic as its cover art. The presence of Cale’s voice – familiar, rich and avuncular – almost disguises just how radical much of the music is. For instance, the glitchy, doomy crawl of “Marilyn Monroe’s Legs (Beauty Elsewhere)”, created in collaboration with Cale’s favourite Actress, is brought into the light by the Welshman’s low croon and high falsetto, flitting hypnotically between a few notes. Even so, it’s the most difficult piece here, as much sound design as song, seven minutes long and positioned up front as track two.

Later in the record, “The Legal Status Of Ice”, featuring Fat White Family and first performed live by Cale and his band pre-pandemic, demonstrates just how far-out Cale is determined to go. It begins as industrial trip-hop with a one-note vocal line and a hip-hop-inspired “pour that liquor out” refrain, before transitioning into brilliant mutant dancehall with descending chords, droning synths and a spitting drum machine. Cabaret Voltaire were inspired by the churn of the Velvets, and here it sounds like Cale is returning the favour.

While Fat White Family’s grubby fingerprints are pretty faint, that’s testament to just how involved Cale is with every facet of Mercy: he plays almost every instrument, with collaborators generally credited with “additional” roles. Weyes Blood’s Natalie Mering is the most obvious contributor, joining Cale on the bad-trip R&B of “Story Of Blood” – her solemn, deep voice occasionally has an air of Nico about it here, which can’t have escaped Cale’s attention.

Two tracks on, he turns to more obvious consideration of his old collaborator on “Moonstruck (Nico’s Song)”, a hyperpop ballad with queasy, unreal strings and a tender refrain about a “moonstruck junkie lady”. As two chords seesaw over an endless sequenced bassline, Cale’s processed vocals mass as he pays a bruised tribute: “I have come to make my peace…” You imagine the song’s subject would have particularly enjoyed the

sub-bass rumble that subsumes the track in its final minute.

It’s not the only time Cale weaves his history into the record either. The video for “Night Crawling”, Mercy’s first single and its most accessible track by a mile, depicts an animated Cale and Bowie cruising around New York’s nightspots, as they did in real life. It’s the only track here that could have fitted on Shifty Adventures…, and it shows how far Cale’s come in the past decade. Amid the electronic sturm und drang, there are musical references to his past too, such as the hymnal chord changes in the middle section of “Time Stands Still”, reminiscent of one of his stately ’70s storytelling ballads, such as Fear’s “Buffalo Ballet”. Elsewhere, the piano intro to “Story Of Blood” is almost identical to the verse melody of that same record’s centrepiece, “Gun”.

Lyrically, he’s in typically opaque form, whether building a song around a handful of conversational lines, or harking back to the disjointed vividness of Paris 1919 – “With the camels standing senseless / From driving through the night” on “Not The End Of The World”, or “The grandeur that was Europe / Is sinking in the mud” on “Time Stands Still”. “I Know You’re Happy”, its lilting chorus and Tei Shi’s melodramatic vocals almost suitable for a TikTok clip, depicts an unequal relationship, the narrator glumly coming to terms with the fact their partner is only content “when I’m sad”.

The final track, one of Mercy’s strongest, finds some hope amid references to suicide and despair. “If you jump out your window / I will break your fall / I’ll hold you close and keep you calm / Wherever you decide to go”, sings Cale over metronomic piano that’s not unlike the musician’s pounding accompaniment on the Velvets’ “I’m Waiting For The Man”. Here, instead of being violent and physical, it’s brutal in a different way: mechanised, relentless and shrouded in thick reverb. At times like this, Mercy recalls the digital distortion of Low’s Double Negative, the clipped onslaught creating its own beauty.

As “Everlasting Days” degrades into claustrophobic drum and bass, with Animal Collective’s vocals cut-up and pitch-shifted, we’re reminded of Bowie’s Blackstar, not only sonically, but in its creator’s audacity and boundless enthusiasm for the new, the strange, the disconcerting. If this were to be the last we hear from Cale – and let’s hope there’s more to come – he’d at least be departing on a triumph, with an uncompromising, thoroughly modern trip into the twilight, to places where even his collaborators and acolytes would fear to tread. Rage, rage.